By Cathy Watson | Chief of Partnerships

When Zakayo and Ludy went to Zambia, they did not know what to expect. Residents of the hardcore, congested, big city of Nairobi ,where they work in the seed bank at ICRAF, they marveled at the wide open spaces. Then they saw the indigenous trees.

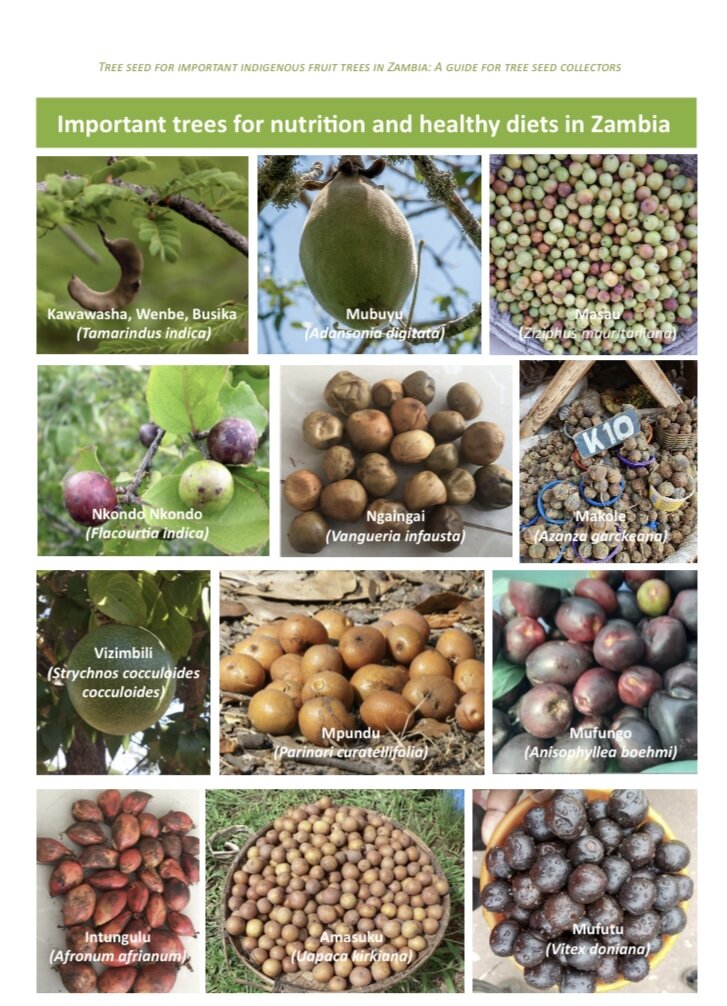

"On our journey from Lusaka to Chipata, I was excited to see Adansonia digitata (Baobab/Mlambe/Kakoma), Flacourtia indica (Nthuza/inkulumbisha), Annona senegalensis (Mpovia), Tamarindus indica (Kawawasha) and Strychnos cocculoides (Ifisingole/ Visimbili/Kabeza)," says Zakayo. "We could not help stopping to collect samples. And we saw their fruits on sale in markets too.”

Once they arrived in Eastern Zambia, where Ludy and Zakayo and colleagues Alfred and Nema were to lead a workshop on tree seed collection, they met the transformed poachers who had been invited -- weary men from communities in poverty who had been unable to find anything else to do. There was even a retired policeman who used to rent out guns.

Fatigue etching their faces, and with very low literacy and little English, they still followed the training with rapt attention. Alfred translated into two Zambian languages - Chichewa and Bemba - one after the other.

The tranformed poachers were clearly hoping that being a tree seed collector might be less dangerous than poaching. One said he had grabbed a lion's tongue to avoid being eaten. Another had climbed a tree to escape hyenas visiting their kill. Others were chased by elephants. All had fled confrontations with wildlife rangers. And some had done time in jail.

"These are people who were merely attempting to feed their families," says Nema who works for ICRAF Zambia. "Like others who attended, they did not know that growing indigenous trees on farms is possible. Yet these trees can provide ‘green’ jobs that can help them cater for their families without risking their lives in the wild.Generally, participants were so eager to learn how they can collect seed for nurseries.”

Charcoal production from trees is another major rural income stream beset by contradictions. People do it to survive but know it contributes to Zambia’s deforestation and climate crisis, which they said is “dwindling” rainfall each year. Charcoal producers among the attendees were relieved that they might be able to plant trees and felt it could be a way to pay back for those they had cut. How to convince other charcoal producers to avoid cutting indigenous fruit/food trees was a question many participants asked.

Women farmers were strong voices at the training too and, as custodians of their families' diets, particularly interested in the trees we were promoting because they could improve diets for their families.

“They felt nostalgic as they recalled their childhood adventures picking fruits in forests while collecting firewood,” says Ludy. “They recalled having plenty of food to eat all year and rarely getting sick. They are worried that these trees are less plentiful now.”

Knowledge of botany is in decline around the world but not in rural communities in Zambia. Our trainees could identify over 20 different native tree species with fruit or other edible parts.

“They knew so much and said Intungulu (Aframomum africanum) is useful for pregnant women,” says Ludy. “Inpundu (Parinari curatelifolia) and baobab/mlambe/kakoma (Adansonia digitata) are good for making porridge. While makole (Azanza garckeana) is highly nutritious and boosts men’s strength.”

While they all liked these native fruits and tree foods, they thought imported apples and oranges were superior. We helped them see the value of their own fruit, and they were left excited about earning an income stream from collecting and selling seed to nurseries, selling the wild fruit in the market, and having these trees on their own land.

We had prepared a manual for them. They were anything but passive receivers. In feedback, they pointed out that we had wrongly labeled a tree and said we should not use a photo of a pickup truck but rather a bicycle, a means of transport they are more likely to have. Only NGOs and businesses have pickups, they said. We will improve the manual for the next training.

This training aimed to equip rural Zambians as well as forestry officials and NGO workers in Eastern Zambia with the knowledge and skills to collect and propagate seed to ensure conservation and multiplication of valuable indigenous fruit and food trees. A project goal is that families can access these trees to boost consumption of vital micronutrients like Vitamins A and D and minerals like calcium and iron.

"The trees will produce for many years with little or no management once they are established," observes Zakayo

"Conserving seed prevents varieties from going extinct," says Ludy. "We will make indigenous tree species available in nurseries, and improve livelihoods in Zambia."

We would like to thank all of you who donated and made this life-changing training possible. You funded three days of learning, including practical seed collection exercises in the forest, and every participant received a certificate on which GlobalGiving was emblazed.

If you can donate again, we will be thrilled, but especially from 3 to 5 April where, in a campaign called Little by Little, GlobalGiving will increase your donation by 50%. So if you donate $25, we receive $37.50 - or if you donate $50, we will receive $75.

This funding will go towards another seed training as well as follow up of the transformed poachers, charcoal makers and farmers. We will keep you posted on how they fare!

Links:

Project reports on GlobalGiving are posted directly to globalgiving.org by Project Leaders as they are completed, generally every 3-4 months. To protect the integrity of these documents, GlobalGiving does not alter them; therefore you may find some language or formatting issues.

If you donate to this project or have donated to this project, you can receive an email when this project posts a report. You can also subscribe for reports without donating.

Support this important cause by creating a personalized fundraising page.

Start a Fundraiser