By Marina Aman Sham | Communications Director, GDF

Oral histories are loosely defined as stories that living individuals, often older members of a family or community, tell about their past, or that of others. The State Library of Western Australia, discussing Aboriginal knowledge systems, calls oral histories the “bridge between oral tradition and written history”. Worldwide, efforts are escalating to capture indigenous oral histories through interviews with community elders, building their voices by sharing their memories, ensuring unique stories are not forgotten.

In Sabah, three consecutive co-inquiry projects with Dusun communities living in the Crocker Range produced research on patterns of local resource use, valuation of landscapes, transmission of indigenous ecological knowledge, and the impact of subsistence strategies on areas adjacent to, or inside, protected areas. Community elders, prompted by local researchers trained over the 8 years of the projects, came forward to reveal tales of heroism and describe events explaining the origins of place names and sacred sites.

Jenny, a community researcher from the remote village of Buayan in the Crocker Range who participated in the projects, continues to advocate for the wellbeing of her community and the preservation of her heritage. Around two years ago, she developed an initiative to add to the list of oral histories already documented through the earlier projects. She interviewed community elders and transcribed these interviews. Armed with three additional stories, she then set out to design multi-lingual posters for each story and a booklet compilation of the stories, using artwork created by Imelda, a university student who also hails from Buayan.

Here are a few short glimpses of two of the oral histories. Interviews were carried out and first documented in the Dusun language; some have already been translated into Malay and English.

"Why Kadui and Sidui?"

[1] “During a time of war between the villages of Kionop and Tiku, two brothers from Kionop village, Sidui and Kadui, were known to be the strongest and most feared warriors.”

[2] “Kadui and Sidui hid themselves and watched quietly, letting Lumingou and Binagal pass them without making any contact.”

[Told by: Angeline Dingon; Documented by: Jiloris Henry]

"Liwat’s Stone"

[1] “Three people – a man named Liwat, the woman he was recently engaged to, and her younger brother, were traveling one day a very long time ago from Kosungu Village, where Liwat was from, to Tudan Buayan, the village of his fiancée.”

[2] “Sudden flashes of lightning occurred, followed by very loud thunder. Liwat and his fiancee turned into stone, as did the equipment they had with them.”

[Told by: Gorumpang Matanggim; Documented by: Jenny]

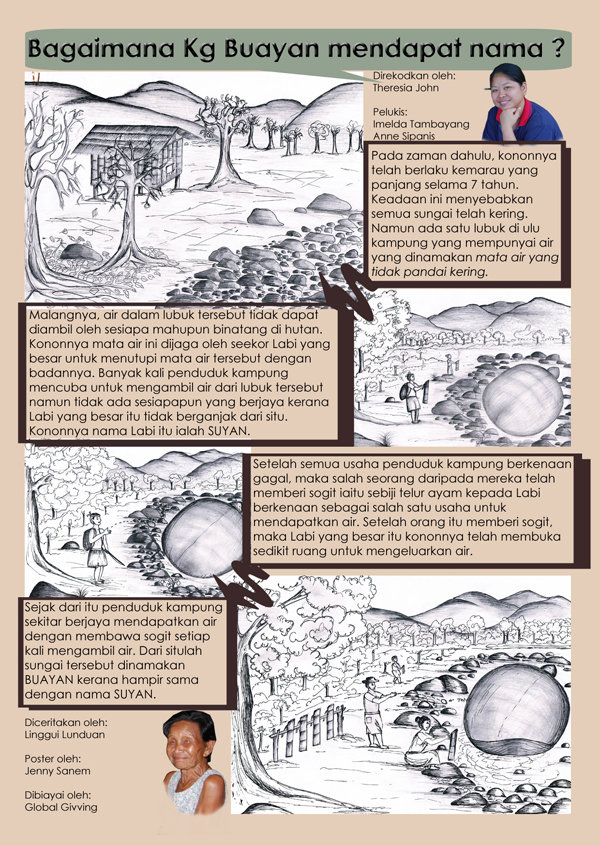

"How did Buayan get its Name?" (draft poster)

[Told by: Linggui Lunduan; Documented by: Therisia John; Artwork by: Imelda, Anne Sipanis; Poster design by: Jenny]

Jenny’s work on her mini-project was exclusively supported by donations made through GlobalGiving. She is now working with Imelda to see this initiative through to its publication, facilitated by Shinobu Majima from Gakushuin University, Japan, through their outreach programme, DISSOLVA. For the last four years, Shinobu has led visiting student groups to Buayan who participated in Dusun community initiatives. DISSOLVA has pledged to support the printing costs of an oral histories publication for the Dusun communities in Ulu Papar.

Links:

By Jenny Sanem | Buayan youth

By Marina Aman Sham | Communications Director, GDF

Project reports on GlobalGiving are posted directly to globalgiving.org by Project Leaders as they are completed, generally every 3-4 months. To protect the integrity of these documents, GlobalGiving does not alter them; therefore you may find some language or formatting issues.

If you donate to this project or have donated to this project, you can receive an email when this project posts a report. You can also subscribe for reports without donating.

![[1] Why Kadui and Sidui?](https://www.globalgiving.org/pfil/10874/Why_Kadui_and_Sidui_1__r_Large.jpg)

![[2] Why Kadui and Sidui?](https://www.globalgiving.org/pfil/10874/Why_Kadui_and_Sidui_2__r_Large.jpg)

![[1] Liwat's Stone](https://www.globalgiving.org/pfil/10874/Liwats_Stone_1__r_Large.jpg)

![[2] Liwat's Stone](https://www.globalgiving.org/pfil/10874/Liwats_Stone_2__r_Large.jpg)