By Michael Webster | Executive Director

Our group of divers had an odd mix of enthusiasm and trepidation as our boat approached a little-known dive site in Roatan Honduras called Cordelia Banks. As the boat tied up to the mooring, we used our polarized sunglasses to get a first glimpse of the reef. Yep, the colors were definitely wrong: not the normally subdued mustard colors, but abnormally bright yellows, blues and whites.

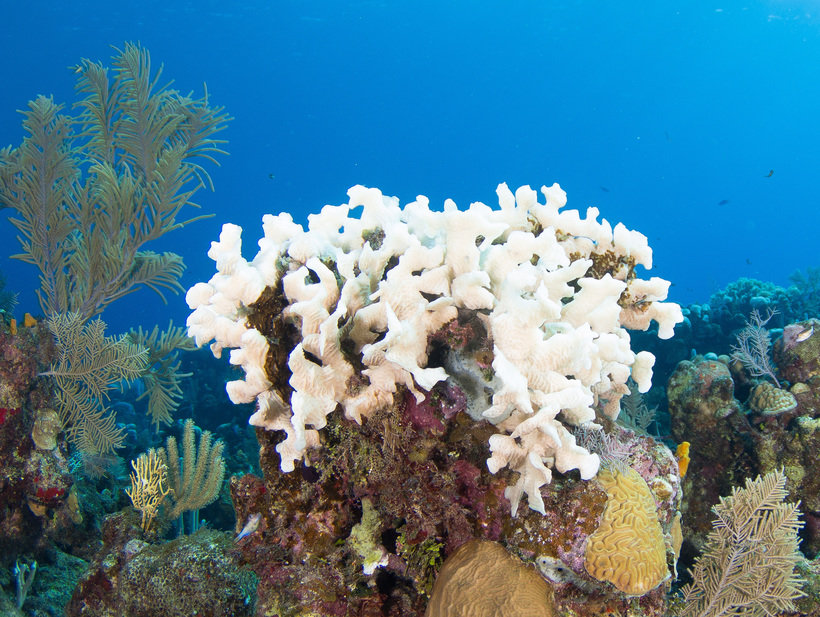

I had been to this site just two months earlier and enjoyed the rare beauty of a Caribbean coral reef with 70 percent live coral cover (the average in the Caribbean is just 18 percent). But the time in-between had been unusually hot and we were getting reports that the corals were starting to bleach. Once we were in the water, we could see that corals everywhere were in the process of changing from rich colors to white. The look on the faces of all the divers was sadness and shock. I even learned a new dive sign for ‘crying in my mask’. This reef, which had been spared significant bleaching for so long, was in the throes of a major bleaching event.

Coral bleaching is something relatively new to science. There are no records of significant bleaching before the 1980s. Since then, bleaching events have gotten more and more common as ocean temperatures continue to rise. When the water gets too warm, the colorful symbiotic algae that live in the tissues of corals and provide food begin to produce toxins instead. In a last-ditch effort by the coral to survive, it expels the algae – its primary food source – and in the process, turns white. Unfortunately, bleaching often means death for many of the corals that build and maintain the reef. However, even amidst the ominous scenes of unnaturally white corals, there are two clear reasons to be optimistic about this reef.

First, not all corals were affected the same way. Many showed no signs of bleaching at all; while most of the others were only partially bleached, they still had some of their color, indicating that their symbiotic algal could regrow quickly if the water cools. This diversity of responses to bleaching means that some corals are naturally better at coping with high temperatures, which is very good news.

Cutting edge research by CORAL and our partners shows that, in fact, this diversity, spread across many reefs in a region, is the key to coral adaptation. By linking diverse reefs together into a large network and reducing local threats, we can create Adaptive Reefscapes, where surviving corals can populate coral reefs within the network with their more tolerant offspring.

Second, local management on this reef is working. Cordelia Banks is part of the Bay Islands National Park and with the hard work of CORAL and our partners, the site we visited was recently designated a no-fishing area. I’ve been visiting this site regularly for the past 6 years and I can see the positive shift in the number and size of fish already. Most importantly, there are more and bigger grazing parrotfish and surgeonfish, which keep seaweeds in check and foster a better environment for baby corals to grow (like the offspring of the heat tolerant survivors!). Right now, this kind of effective management is one of the absolute best things we can do to help corals adapt and recover from bleaching.

While it’s too early to know how this particular bleaching event will play out, we are working with our partners in Honduras to actively monitor how the reefs respond and recover. We are also encouraged to see that the water has already started to decrease in temperature, helped by several storms that block the sunlight and add cooler rainwater.

We recognize that we can’t stop coral bleaching entirely until we tackle climate change, but in the meantime, there’s a whole lot we can do to help corals adapt to the immediate challenges in their environment, and Cordelia Banks gives me real hope. It shows how effective management can help reefs recover from bleaching as well as how much diversity is already out there. It also shows how dedicated communities can band together to help their coral reefs adapt and survive in a rapidly changing world — and win.

Article first published in the Huffington Post October 31, 2017

By James Lloyd | Communications Manager

By James Lloyd | Communications Manager

Project reports on GlobalGiving are posted directly to globalgiving.org by Project Leaders as they are completed, generally every 3-4 months. To protect the integrity of these documents, GlobalGiving does not alter them; therefore you may find some language or formatting issues.

If you donate to this project or have donated to this project, you can receive an email when this project posts a report. You can also subscribe for reports without donating.

Support this important cause by creating a personalized fundraising page.

Start a Fundraiser